25 Jan 2026

- 0 Comments

When you look up at the moon on a clear night, you’re not just seeing a glowing disk-you’re staring at a frozen record of our solar system’s early history. The moon’s surface holds clues no Earth rock can give us. Without wind, water, or plate tectonics, the lunar surface preserves impacts, lava flows, and ancient crust that formed over 4 billion years ago. But what exactly are these rocks made of? And how do scientists know how old they are? The answers lie in the rocks brought back by Apollo astronauts and later studied by robotic missions.

What Are the Main Types of Moon Rocks?

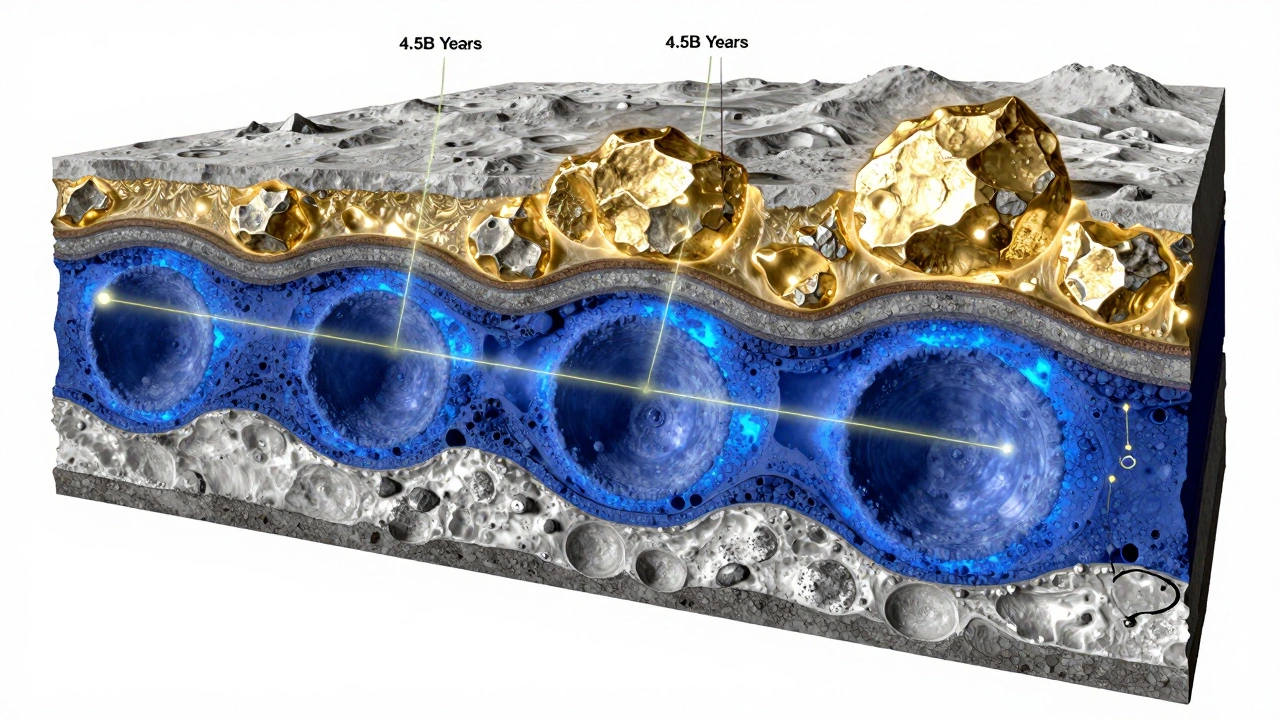

The moon isn’t covered in one kind of rock. It has two dominant types, each telling a different story. The first is highland rocks, which make up the bright, cratered areas you see with the naked eye. These are mostly anorthosite-a rock made almost entirely of the mineral plagioclase feldspar. Anorthosite forms when molten rock cools slowly, allowing light-colored minerals to float to the top. Scientists believe this layer formed the moon’s original crust, solidifying just 100 million years after the moon itself formed.

The darker patches you see? Those are lunar maria, or “seas.” They’re not water-they’re ancient lava plains. The rocks here are basalt, similar to the volcanic rock found in Hawaii or Iceland, but with key differences. Lunar basalt has more iron and titanium, and almost no water. It erupted from deep inside the moon between 3 and 3.5 billion years ago, flooding giant impact basins like Mare Imbrium and Oceanus Procellarum. These flows were thick, sometimes over a mile deep, and cooled slowly enough to form large crystals visible under a microscope.

There’s also a third, rarer type: breccia. These are broken, smashed-up rocks fused together by meteorite impacts. Apollo astronauts found breccias everywhere, especially near impact craters. They’re like lunar conglomerates-pieces of highland rock, basalt, and even glassy fragments welded together by the heat of collisions. Breccias are the moon’s version of a geological scrapbook, recording every major impact over billions of years.

How Do Scientists Date Moon Rocks?

On Earth, we use radiocarbon dating for organic material, but moon rocks are completely inorganic. Instead, scientists use radioactive decay of elements like uranium, thorium, and potassium. These elements decay into lead at known, constant rates. By measuring the ratio of parent isotopes to daughter isotopes in a rock sample, researchers can calculate its age with incredible precision.

The oldest lunar rocks-found in the highlands-clock in at about 4.5 billion years. That’s nearly as old as the solar system itself. These rocks formed when the moon was still molten, and heavier minerals sank while lighter ones floated to form the crust. The youngest basalt flows? Around 3 billion years old. That’s surprising. We used to think lunar volcanism died out 3.5 billion years ago, but recent studies of samples from China’s Chang’e 5 mission found basalt as young as 2 billion years. That means the moon’s interior stayed hot and active far longer than anyone expected.

One key method used is argon-argon dating. A tiny grain of lunar basalt is zapped with a laser in a vacuum chamber, releasing trapped argon gas. The amount of argon-40, produced by potassium decay, tells scientists exactly how long it’s been since the rock cooled. This technique has been refined over decades and is now used on samples from every major lunar mission.

Why Does the Moon’s Surface Age Vary So Much?

Not all parts of the moon are the same age. The bright highlands are ancient, heavily cratered, and full of impact scars. The dark maria are younger, smoother, and have far fewer craters. Why? Because lava flows buried the older craters. Think of it like painting over an old mural-the new layer hides what’s underneath.

Scientists count craters to estimate age. More craters = older surface. This method, called crater density dating, works because meteorite impacts have happened at a fairly steady rate across the solar system. A surface with 100 craters per square kilometer is likely older than one with 10. The lunar highlands have over 1,000 craters per square kilometer. The maria? Maybe 100 to 200. That’s why we know the maria formed later.

But there’s a twist. Some areas on the moon have unusual crater patterns. The south pole-Aitken Basin, the largest and oldest impact crater in the solar system, has a surface that looks younger than it should. Why? Because the impact that formed it dug so deep it brought up material from the moon’s mantle. That material was later covered by younger lava, making the surface appear artificially young. This is why surface age doesn’t always match rock age.

What Can Moon Rocks Tell Us About Earth?

The moon and Earth share a common origin. About 4.5 billion years ago, a Mars-sized object smashed into the young Earth. The debris from that collision coalesced into the moon. That’s why lunar rocks have nearly identical oxygen isotopes to Earth’s mantle-they came from the same source.

But while Earth’s surface gets recycled by plate tectonics and erosion, the moon’s surface has been a silent witness. Lunar rocks preserve the chemical signature of the early solar system. For example, lunar basalts contain higher levels of titanium than Earth’s basalts, suggesting the moon’s interior was more chemically distinct. Studying these differences helps us understand how planets differentiate into core, mantle, and crust.

Also, the moon holds no evidence of early life, no oceans, no atmosphere. That makes it a perfect control sample. If we find organic compounds or water trapped in lunar glass beads, we can ask: Did they come from the moon’s interior, or were they delivered by comets? That question helps us understand how water got to Earth.

The New Frontier: Lunar Samples Beyond Apollo

The Apollo missions brought back 382 kilograms of moon rock between 1969 and 1972. But those samples came from just six locations near the equator. We’ve spent decades trying to fill the gaps. In 2020, China’s Chang’e 5 mission landed in the northern part of Oceanus Procellarum and returned 1.7 kilograms of material. The rocks there were 2 billion years old-much younger than any Apollo sample.

These new samples are changing textbooks. They show that the moon’s volcanic activity lasted longer than models predicted. They also contain tiny glass beads with water molecules trapped inside, suggesting water may have been present in the moon’s mantle. This contradicts the old belief that the moon was bone-dry.

Future missions, like NASA’s Artemis III, plan to land near the south pole, where permanently shadowed craters may hold ice. The rocks there could be even older than the highlands, possibly dating back to the moon’s formation. If we can bring back samples from those regions, we’ll get a clearer picture of how the moon-and by extension, Earth-formed.

What’s Next in Lunar Geology?

There’s still so much we don’t know. Why did lunar volcanism stop in some places but continue in others? What’s hidden beneath the far side? How deep did the giant impacts really go? New instruments on orbiters like NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter are mapping the moon’s gravity, heat flow, and mineral composition in unprecedented detail. But ground truth-the real answer-comes from rocks.

The next big leap will come when we drill into the moon’s surface, not just scoop up surface dust. Future lunar bases could host labs that analyze samples in real time, avoiding contamination from Earth. Imagine being able to test a rock for water content, mineral structure, and isotopic ratios on the moon itself. That’s not science fiction-it’s the next step.

The moon’s rocks aren’t just rocks. They’re time capsules. Each one holds a story of fire, collision, and quiet cooling across billions of years. By understanding them, we’re not just learning about the moon-we’re learning how rocky planets begin.

What are the three main types of moon rocks?

The three main types are anorthosite (highland rocks), basalt (lunar maria), and breccia (impact-fused fragments). Anorthosite forms the ancient crust, basalt fills old impact basins with lava, and breccia is made of shattered rock glued together by meteorite impacts.

How do scientists know the age of moon rocks?

They use radiometric dating, especially argon-argon and uranium-lead methods. These measure how much radioactive elements like potassium and uranium have decayed into stable isotopes like argon and lead. The ratio tells them how long ago the rock cooled and solidified.

Are all parts of the moon the same age?

No. The bright highlands are the oldest, around 4.5 billion years. The dark maria are younger, mostly 3 to 3.5 billion years old, but recent samples show some lava flows as young as 2 billion years. Surface age is also estimated by counting craters-more craters mean older terrain.

Why are lunar rocks important for understanding Earth?

The moon and Earth formed from the same material after a giant impact. Lunar rocks preserve conditions from the early solar system that Earth’s active geology has erased. Studying them helps us understand planetary formation, how water arrived on Earth, and why planets develop different layers.

What did the Chang’e 5 mission discover?

Chang’e 5 returned basalt samples from Oceanus Procellarum dated at 2 billion years old-much younger than Apollo samples. This showed lunar volcanism lasted longer than expected. The samples also contained tiny glass beads with trapped water, challenging the idea that the moon was completely dry.