10 Jan 2026

- 0 Comments

Ever wonder what the night sky will look like in 50 years? Or maybe you’re curious how the stars will shift during a total eclipse next decade? Planetarium software lets you jump forward - or backward - in time to see the heavens exactly as they’ll appear. But none of that works without one key feature: accurate time and date controls.

Why Time and Date Matter More Than You Think

Stars don’t just sit still. Planets crawl across the sky. The Moon wobbles. Constellations slowly rotate over centuries. If your planetarium app treats today like forever, you’re not seeing the real universe - you’re seeing a photo.

Modern planetarium software like Stellarium, SkySafari, and Cartes du Ciel doesn’t just show you the sky. It calculates where every object should be based on physics, orbital mechanics, and centuries of observational data. That means every second you change the date or time, the software recalculates positions down to the arcsecond. It’s not magic. It’s math - and it’s why getting the time controls right matters more than the resolution of your screen.

How Time Controls Actually Work

Most planetarium programs give you three ways to adjust time:

- Real-time playback: The sky moves as it does in nature - one minute per minute. Useful for watching a lunar eclipse unfold.

- Fast-forward: Speed up time by 10x, 100x, even 10,000x. Great for seeing how Mars moves over weeks in seconds.

- Jump to exact date/time: Type in a date - say, July 15, 2047 - and the software instantly snaps to that moment. This is how you plan for future eclipses or planetary alignments.

Behind the scenes, these tools rely on the Julian Date is a continuous count of days since January 1, 4713 BCE. Every planetarium app converts your chosen date into a Julian Date, then uses that number to compute positions using the VSOP87 and a mathematical model for planetary motion developed in 1987 and still used today formulas. Even your phone’s star map uses this system - just hidden behind a simple slider.

Setting the Right Date: Common Mistakes

It sounds simple: pick a date. But people mess this up all the time.

- Forgetting time zones: If you set the date to January 1, 2030, but leave the time at UTC+0 while you’re in Los Angeles, the sky will be off by hours. Always sync your software’s time zone with your location.

- Using the wrong calendar: Some apps default to the Gregorian calendar. But if you’re simulating skies from 1582, you might need to toggle to the Julian calendar - because that’s when Europe switched. Miss this, and your Mars position will be wrong by days.

- Ignoring leap seconds: Earth’s rotation slows slightly over time. Since 1972, 27 leap seconds have been added to keep atomic time in sync with solar time. Most serious planetarium software accounts for this. If yours doesn’t, it’s outdated.

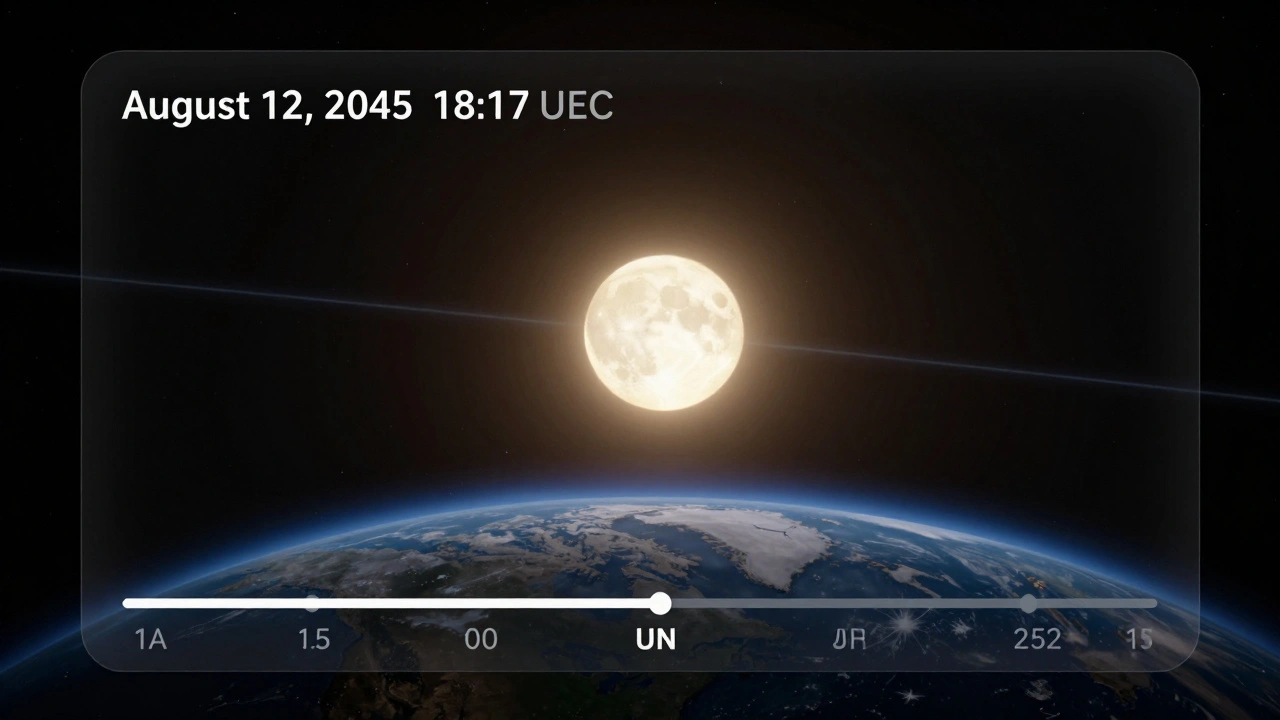

For example, if you want to see the 2045 total solar eclipse over the U.S., you need to set the exact time: 18:17 UTC on August 12, 2045. Get that wrong by 10 minutes, and you’ll miss the moment of totality. The software will show the Moon just missing the Sun - and you’ll think the simulation is broken.

Simulating the Future: What You Can Actually See

Planetarium software can simulate skies thousands of years into the future - but not everything is equally accurate.

Planets? Highly accurate. Their orbits are stable over millennia. You can reliably see Jupiter’s moons in 2150.

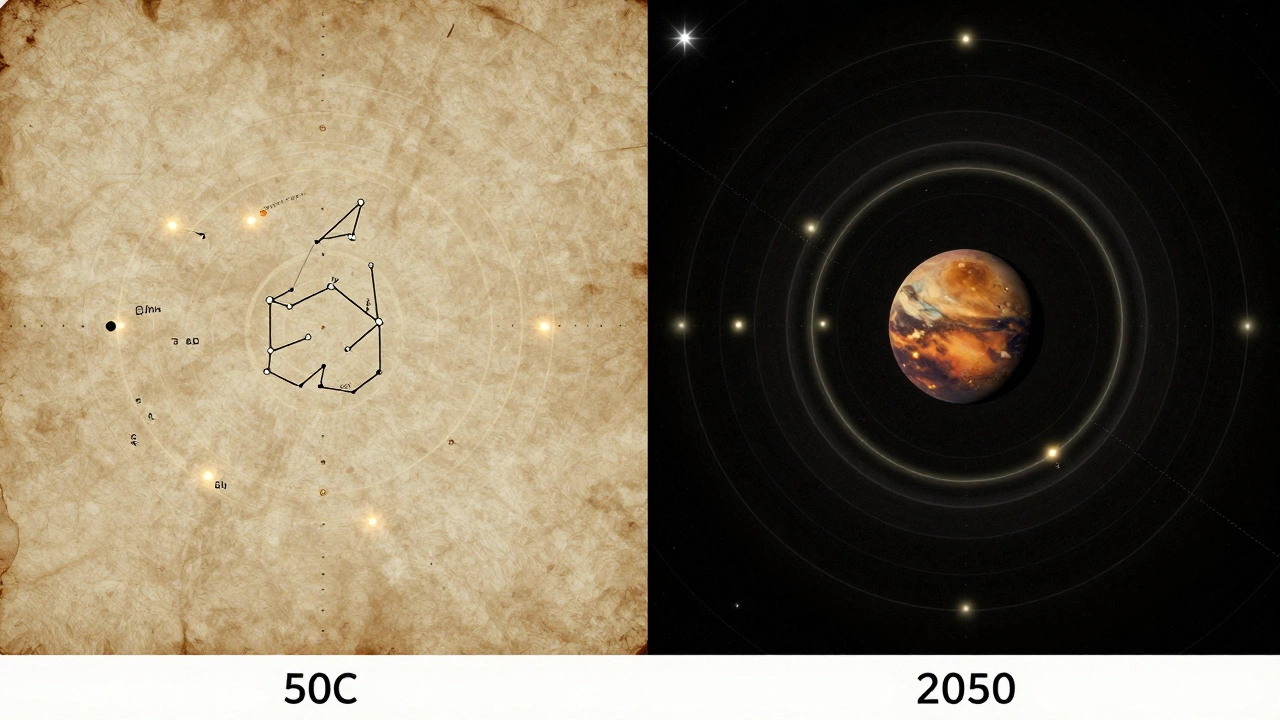

Stars? Less so. Stars move. Vega will be the North Star around 13,727 AD - but that’s 11,700 years from now. Most apps can’t simulate star motion beyond 10,000 years because we don’t have precise enough proper motion data. The software will guess - and guess wrong.

Comets and asteroids? Unreliable. Their orbits change due to gravity from planets, solar wind, even outgassing. A comet like Halley is predictable - it returns every 76 years. But a new one, like C/2023 A3, might break apart or veer off course. Planetarium software can only simulate based on its last known path.

That’s why astronomers use these tools not to predict the future, but to test hypotheses. If a simulation shows a rare alignment in 2078, they go back to telescope data. Did we miss something? Is there a gravitational tug we didn’t account for? The software doesn’t answer the question - it just shows you what to look for.

Real-World Use Cases

People don’t just use this for fun. Here’s how it’s actually applied:

- Event planning: A public observatory wants to host a viewing of the 2034 lunar eclipse. They use the software to confirm visibility from their location, time the event perfectly, and even generate a sky map for attendees.

- Education: A high school teacher simulates the sky as seen from ancient Babylon in 500 BCE to show how early astronomers tracked Venus.

- Space mission design: NASA engineers use similar tools to simulate how the stars will appear from Mars during a rover’s landing in 2031 - helping calibrate navigation cameras.

- Art and film: Sci-fi filmmakers use planetarium software to make alien skies look real. The planet in Interstellar was modeled using real orbital data from exoplanet catalogs.

One astrophysicist I spoke to said he once used the software to prove that a 1970s telescope photo of a star cluster was mislabeled. The stars had moved. The date on the photo didn’t match the positions. The software caught it in seconds.

What to Look for in Time Controls

Not all planetarium software handles time the same way. Here’s what to check before you pick one:

- Support for Julian Date input: If you can type in a Julian Date directly, you’re working with professional-grade tools.

- Calendar toggle: Can you switch between Gregorian and Julian calendars? Essential for historical simulations.

- Leap second handling: Check the documentation. If it’s not mentioned, assume it’s ignored.

- Time zone auto-detection: Does it read your system settings? Or do you have to manually pick it every time?

- Accuracy range: Does it claim to work for dates before 1000 BCE or after 10,000 CE? If so, verify the source of its data. Many apps just extrapolate.

Stellarium, for example, supports dates from 9,999 BCE to 9,999 CE. But its star positions beyond 10,000 years are estimated. SkySafari 7 limits you to 10,000 years ahead, but uses actual proper motion data from the Gaia satellite - making it more accurate for stars.

Limitations and What You Can’t Simulate

There are things even the best software can’t do:

- Changes in Earth’s tilt: Over 41,000 years, Earth’s axis wobbles. That changes which stars are pole stars. Most apps don’t model this.

- Supernovae: If a star explodes tomorrow, the software won’t know. It only knows what we’ve cataloged.

- Exoplanet atmospheres: You can see where Proxima b is in 2050, but you can’t simulate its clouds or weather. That’s beyond current science.

- Human-made objects: Satellites, space stations, and debris move unpredictably. Most apps don’t track them in real time.

Think of planetarium software like a weather app for the stars. It’s great for forecasting - but don’t expect it to predict a tornado.

Next Steps: Try It Yourself

Download Stellarium (free) or SkySafari (iOS/Android). Set the date to January 1, 2050. Turn on the ecliptic line. Watch how Mars moves against the background stars. Now jump to June 1, 2048 - that’s when Mars will be closest to Earth in this decade. See how bright it gets? That’s the power of accurate time controls.

Try simulating the sky from your birth date. Or your child’s birth date, 20 years from now. You’ll see how the universe keeps moving - even when we don’t.

Can planetarium software show the sky from another planet?

Yes, but only if the software supports it. Stellarium and SkySafari let you change your viewing location to Mars, Jupiter’s moons, or even exoplanets. The sky looks completely different - stars shift, the Sun’s position changes, and familiar constellations vanish. But the time and date controls still work the same way: you set the date, and the software calculates positions relative to that location.

Why does the Moon sometimes appear in the wrong place in my simulation?

The Moon’s orbit is complex. It’s pulled by both Earth and the Sun, and its path wobbles. If your software doesn’t use high-precision lunar models (like the ELP/MPP02), it will drift over time. For accurate lunar positions, use software that references NASA’s JPL ephemerides. Otherwise, expect errors of up to 10 degrees over several years.

Do I need internet to simulate future skies?

No. Once you’ve downloaded the star and planet data, planetarium software works offline. The calculations are done locally using built-in algorithms. Internet is only needed to update the catalog or download new data - not to run the simulation.

How far into the future can I realistically simulate?

For planets and the Sun, up to 10,000 years ahead with high accuracy. For stars, accuracy drops after 1,000 years because we don’t have precise enough motion data. Beyond 10,000 years, most software just extrapolates - so positions become guesses. For anything beyond that, you’re in speculative territory.

Can I simulate eclipses hundreds of years from now?

Yes. Solar and lunar eclipses are among the most predictable events in astronomy. NASA’s JPL ephemerides can forecast them accurately for over 10,000 years. You can simulate the next total solar eclipse visible from New York - not just next year, but in 2187. The timing and path will be correct.