26 Dec 2025

- 0 Comments

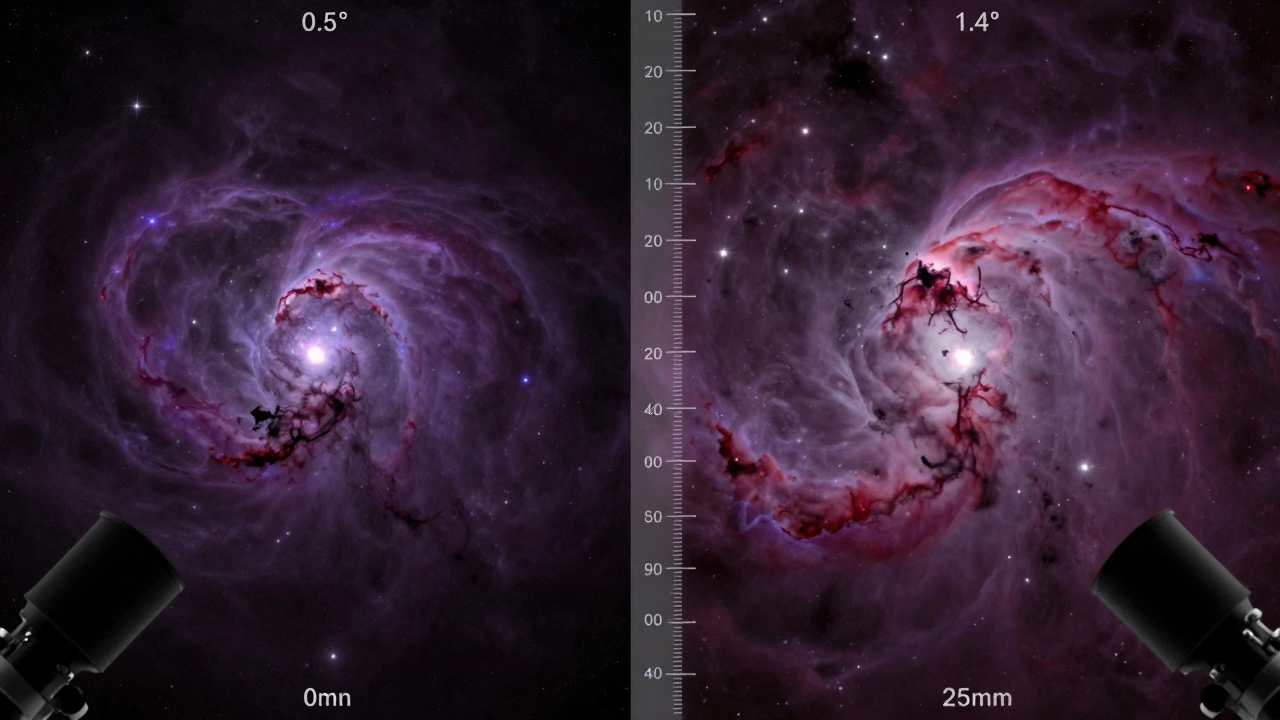

Ever pointed your telescope at the Pleiades and wondered why only half the cluster fit in the eyepiece? Or tried to catch the whole Orion Nebula and ended up with just its glowing core? It’s not your eyes - it’s the math. Every telescope and eyepiece combo shows you a specific slice of the sky, called the field of view. Knowing how to calculate it means you won’t waste time chasing objects that don’t fit - and you’ll find the perfect setup for whatever you’re looking at.

What Exactly Is Field of View?

Field of view (FOV) is the circular area of the sky you see through your telescope. Think of it like looking through a window. A wide window lets you see more of the backyard. A narrow one shows just the flowerpot. In astronomy, that window is defined by your telescope’s focal length and the eyepiece you’re using. There are two kinds you need to know: apparent field of view and true field of view.

Apparent field of view (AFOV) is how wide the eyepiece feels when you look into it. Most eyepieces have an AFOV printed on them - usually between 40° and 82°. A 40° eyepiece feels tight, like looking through a straw. A 82° eyepiece feels open, like staring out a large window. But that’s not the whole story. The real number - the true field of view (TFOV) - tells you exactly how much sky you’re seeing.

The Formula: True Field of View = Apparent Field ÷ Magnification

You don’t need a PhD to calculate this. The math is simple:

True Field of View (TFOV) = Apparent Field of View (AFOV) ÷ Magnification

That’s it. But you need to know two things: your eyepiece’s AFOV and the magnification your setup gives you.

Magnification is easy too: Magnification = Telescope Focal Length ÷ Eyepiece Focal Length

Example: You’ve got a telescope with a 1200mm focal length and a 10mm eyepiece with a 68° apparent field. First, find magnification: 1200 ÷ 10 = 120x. Then, plug into the FOV formula: 68° ÷ 120 = 0.57°. So your true field of view is about half a degree.

What does half a degree mean? The full moon is about 0.5° across. So with that setup, you’re seeing an area of sky roughly the size of the moon. That’s perfect for the Moon itself, or a tight cluster like M13. But you won’t fit the whole Andromeda Galaxy - it’s over 3° wide.

How to Find Your Eyepiece’s Apparent Field

Not all eyepieces list their AFOV clearly. If yours doesn’t, here’s how to find it:

- Check the manufacturer’s website - most list specs online.

- Look for model names: “Ultra Wide Angle,” “Nagler,” “Ethos” - these usually mean 80°+.

- Common AFOVs: Plössl (45°-52°), Erfle (60°-65°), Tele Vue Delos (72°), Tele Vue Nagler (82°), Explore Scientific 82° (82°).

If you’re stuck, assume 50° for older Plössl eyepieces. It’s not perfect, but it’s close enough to get you started.

Real-World Examples: What Fits Where?

Let’s say you’re using a common 8-inch Dobsonian with a 1200mm focal length. Here’s what different eyepieces show you:

| Eyepiece Focal Length | Apparent FOV | Magnification | True FOV | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25mm | 50° | 48x | 1.04° | Orion Nebula, Pleiades |

| 15mm | 68° | 80x | 0.85° | Galaxies, double stars |

| 10mm | 82° | 120x | 0.68° | Planets, tight clusters |

| 6mm | 82° | 200x | 0.41° | Planets, lunar details |

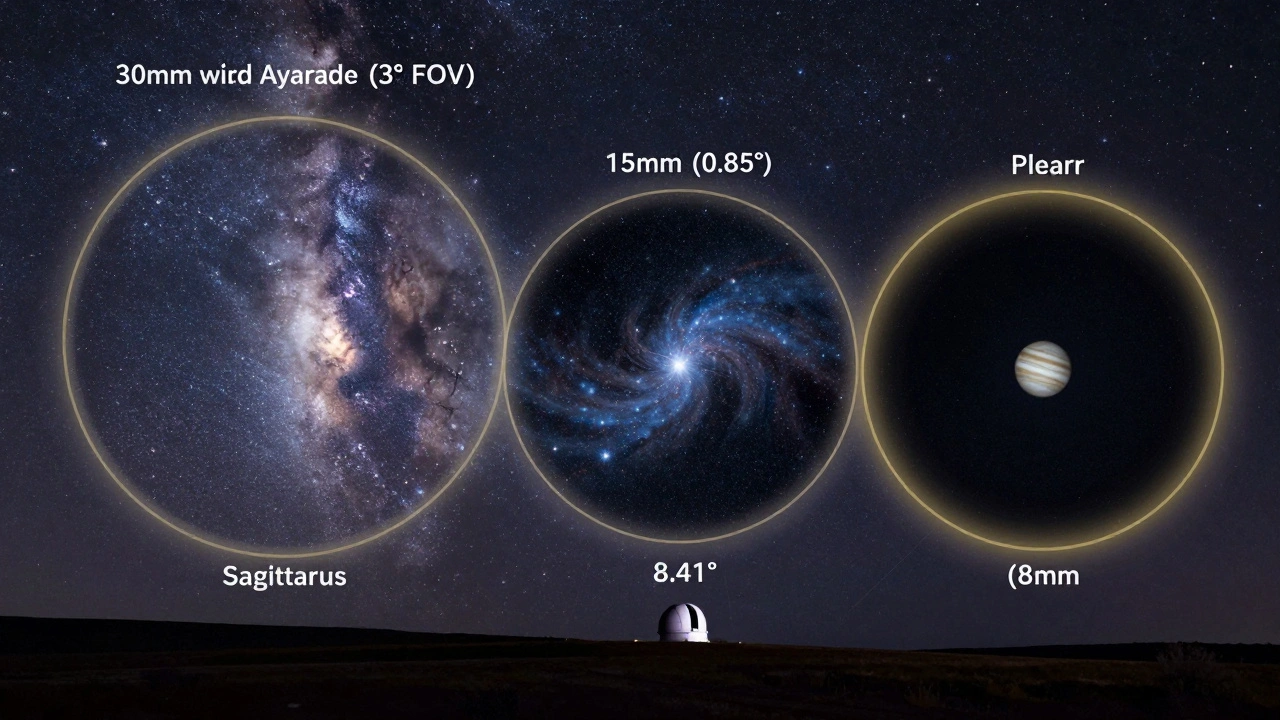

Notice how the 25mm eyepiece gives you a 1.04° field - wide enough to fit the whole Pleiades cluster. That’s a crowd-pleaser. The 6mm? Only 0.41°. You’ll see Jupiter’s moons clearly, but you’ll miss the whole disk of Jupiter’s cloud bands. You need to match the FOV to the object.

Why This Matters More Than You Think

Most beginners buy a telescope, then grab the cheapest eyepieces. They end up frustrated. “Why can’t I see the whole thing?” they ask. The answer is almost always: your field of view is too narrow.

Wide-field objects like the North America Nebula, the Coathanger Cluster, or even the Milky Way’s dense band near Sagittarius need at least 1.5° to 3° to show properly. If your setup gives you less than 1°, you’re missing most of the beauty.

On the flip side, planets need high magnification - but even there, a too-narrow FOV makes it hard to find them. A 0.3° field is like trying to thread a needle in the dark. Start with a wider view, center the planet, then switch to a higher-power eyepiece.

Tools to Help You Skip the Math

You don’t have to calculate everything by hand. Free apps like Stellarium or SkySafari let you simulate your telescope setup. Just enter your telescope’s focal length and the eyepiece specs - and it shows you exactly what the sky will look like through your scope. It’s like a preview.

Or use a simple online calculator. Search “telescope field of view calculator” - dozens of them exist. Plug in your numbers, and it spits out TFOV in degrees or arcminutes. Even better: some give you a visual overlay of how the object fits.

Pro Tip: Use a Finder Scope

If you’re struggling to find objects, your finder scope matters too. A 6x30 finder shows a 6°-7° field - wide enough to navigate the sky. But if you upgrade to a 9x50 or a red-dot finder, you’ll find things faster. Always align your finder with your main scope. A misaligned finder is like using a GPS with wrong coordinates.

What If You Want to See the Whole Orion Nebula?

The Orion Nebula stretches about 1° across. That’s big - bigger than the full moon. To see it all at once, you need a TFOV of at least 1.2°.

With a 1200mm scope, you’d need a 25mm eyepiece with 68° AFOV (TFOV = 68 ÷ 48 = 1.42°). Perfect. Or use a 32mm Plössl (50° AFOV): 50 ÷ 37.5 = 1.33°. Also works.

But if you’re using a 2000mm scope? Same 25mm eyepiece gives you 80x magnification. TFOV = 68 ÷ 80 = 0.85°. Now you’re cutting off the edges. You’d need a 40mm wide-angle eyepiece to get back to 1.2°.

Longer focal length telescopes aren’t bad - they’re just better for planets. For deep-sky objects, shorter focal lengths (under 1000mm) are more forgiving.

Don’t Forget: Atmospheric Conditions Change Everything

Even with perfect math, your view depends on the sky. High humidity? Clouds? Light pollution? Wind? These don’t change the FOV - but they change what you can actually see.

On a bad night, even a 2° field might look empty. On a crystal-clear night in the mountains, that same setup will show you stars you never knew existed. That’s why experienced observers keep multiple eyepieces. One for wide views, one for detail, and one for when the air is steady.

Final Rule of Thumb

Here’s a quick cheat sheet:

- Objects smaller than 0.5° (planets, double stars, tight clusters) → Use 10mm-15mm eyepieces.

- Objects 0.5°-2° (Orion, Pleiades, Andromeda core) → Use 20mm-25mm with 60°+ AFOV.

- Objects larger than 2° (Milky Way, large nebulae) → Use 30mm+ with 70°+ AFOV, or a low-power wide-field lens.

And remember: you don’t need 10 eyepieces. Start with three: a wide one (30mm), a mid-range (15mm), and a high-power one (8mm). That covers 90% of what you’ll ever look at.

How do I find my telescope’s focal length?

Check the telescope’s manual or the label on the optical tube. Most telescopes list it directly - often as “FL: 1200mm” or similar. If you can’t find it, multiply the aperture (in mm) by the focal ratio. For example, an f/10 scope with 200mm aperture has a focal length of 200 × 10 = 2000mm.

Can I calculate FOV without knowing the eyepiece’s apparent field?

Yes - but it’s less accurate. You can estimate the true field by measuring how long it takes a star to drift across the center of the eyepiece. Time the drift in seconds, then divide by 240 to get degrees. For example, if a star takes 120 seconds to cross the field, your FOV is 120 ÷ 240 = 0.5°. This works best on nights with steady air.

Why does my wide-field eyepiece show blurry edges?

That’s normal with cheaper eyepieces. Wide fields require complex lens designs. Budget Plössls or basic wide-angles often suffer from edge distortion. If the center is sharp but the corners are soft, upgrade to a better design - like a Tele Vue Panoptic or Explore Scientific 82°. They cost more, but the view is worth it.

Do Barlow lenses change the field of view?

Yes. A 2x Barlow doubles magnification, which cuts your true field of view in half. A 32mm eyepiece with 50° AFOV gives you 1.25° FOV. Add a 2x Barlow? Now you’re at 16mm effective focal length and 0.625° FOV. You gain detail, but lose sky. Use Barlows for planets - not for wide-field objects.

What’s the widest field I can get with a standard telescope?

The widest practical field for most backyard scopes is around 3°-4°. That usually requires a 40mm-50mm eyepiece with 70°+ AFOV on a short focal length scope (under 700mm). Telescopes like the Astro-Physics 130mm f/5 or the SkyWatcher 150mm f/5 are built for this. They’re ideal for sweeping the Milky Way or catching large nebulae like the Veil.

If you’ve ever stared into the eyepiece and thought, “I wish I could see more,” now you know how to make that happen. It’s not magic - it’s math. And once you understand it, your telescope stops being a mystery and starts being a tool - precise, powerful, and perfectly tuned to what you want to see.