2 Jan 2026

- 0 Comments

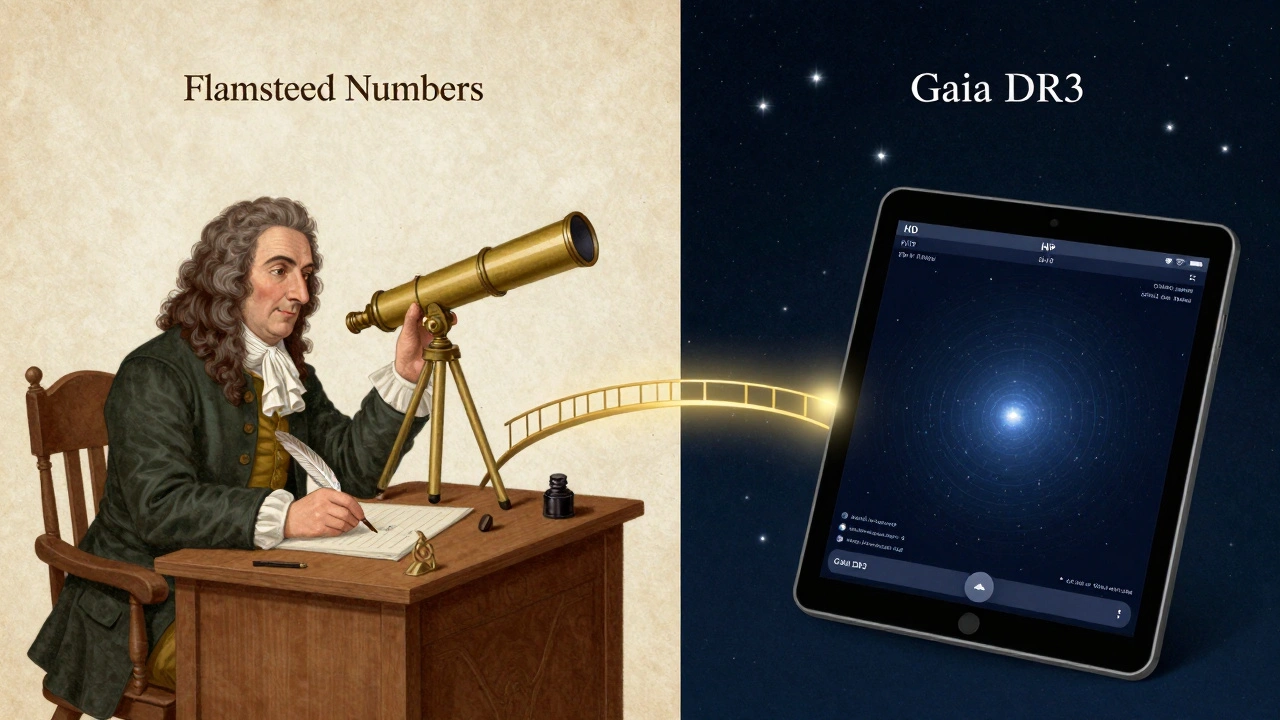

Ever stared up at the night sky, tried to find a specific star, and felt completely lost even though you had a star chart in hand? You’re not alone. Many amateur astronomers hit a wall when they see numbers like 47 Cygni or 61 Ursae Majoris and wonder what they mean. These aren’t random labels-they’re Flamsteed numbers, a centuries-old system still used today alongside modern catalogs. Learning how to read them turns a confusing map into a reliable guide.

What Are Flamsteed Numbers?

Flamsteed numbers are a way to label stars within each constellation, based on their position from west to east. They were created by John Flamsteed, England’s first Astronomer Royal, in the early 1700s. He compiled the first detailed star catalog using a telescope, which was a big deal back then. Before that, stars were mostly named by Arabic or Greek traditions, like Vega or Betelgeuse. Flamsteed’s system gave each star a number and its constellation name-like 51 Pegasi or 101 Herculis.

Here’s how it works: Within a constellation, stars are numbered in order of increasing right ascension (essentially, their position moving eastward across the sky). So, the westernmost star in a constellation gets the lowest number. That’s why 1 Canis Majoris sits near the western edge of the constellation, while 70 Canis Majoris is farther east. These numbers aren’t about brightness-they’re about location.

Flamsteed cataloged 3,000 stars, mostly visible from the Northern Hemisphere. His work was published posthumously in 1725 as Historia Coelestis Britannica. Today, you’ll still see these numbers printed on paper star charts, in older astronomy books, and even in some planetarium apps.

Why Flamsteed Numbers Still Matter

You might think modern astronomy has replaced Flamsteed numbers with something better-and you’re right, partially. But they haven’t disappeared. Why? Because they’re practical.

When you’re holding a printed star chart from the 1980s or using an app that hasn’t been updated in years, Flamsteed numbers are often the only labels you’ll see. If you’re trying to find a star like 16 Lyrae, and your app only shows Bayer letters (like γ Lyrae), you’ll be stuck. Knowing how to cross-reference Flamsteed numbers with modern catalogs saves time and frustration.

Also, many variable stars and double stars still carry Flamsteed designations in professional literature. For example, 61 Cygni is famous as the first star to have its distance measured using parallax-in 1838. That’s still called 61 Cygni, not some alphanumeric code from a modern survey.

Plus, Flamsteed numbers are easy to remember. 78 Ursae Majoris is easier to recall than HD 103095 or HIP 58173. In the field, you don’t want to be flipping through a catalog every time you look up.

Modern Star Catalogs You Should Know

Today, astronomers rely on digital catalogs that are far more precise. Here are the three most important ones you’ll run into:

- Henry Draper Catalog (HD)-Created in the early 1900s, this catalog assigns numbers based on right ascension, like Flamsteed, but includes over 225,000 stars. It’s still widely used for spectral classification. So HD 209458 is the same star as 51 Pegasi.

- Hipparcos Catalog (HIP)-Launched in 1989, this satellite measured the positions and distances of over 118,000 stars with unprecedented accuracy. If you’re doing precise star-hopping or astrometry, you’ll need HIP numbers. HIP 98467 is the identifier for 51 Pegasi.

- Gaia Catalog (Gaia DR3)-The latest and greatest. Gaia’s third data release (2022) includes over 1.8 billion stars, with positions, motions, brightness, and even chemical compositions. It’s the gold standard now. Gaia DR3 58477458745687232 is the full identifier for 51 Pegasi.

These catalogs don’t replace Flamsteed numbers-they complement them. Think of Flamsteed as the friendly nickname and HD/HIP/Gaia as the official ID card.

How to Match Flamsteed Numbers to Modern Catalogs

Here’s how to bridge the gap between old and new:

- Start with the Flamsteed designation: 47 Cygni.

- Use a free tool like Simbad (in your browser) or an astronomy app like Stellarium. Type in "47 Cygni".

- The result will show you the HD number: HD 202540, the HIP number: HIP 104888, and the Gaia ID.

- Now you can use any of those numbers to look up the star’s current position, brightness, or distance.

For example, if you’re trying to observe 14 Andromedae and your telescope’s database only accepts HD numbers, you’ll need to convert it. Without knowing how to cross-reference, you’d miss it entirely.

Pro tip: Many astronomy apps now let you toggle between naming systems. Turn on Flamsteed labels in your app settings-it makes star-hopping much easier if you’re using a paper chart.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Even experienced stargazers make these errors:

- Assuming higher number = brighter star-Flamsteed numbers are positional, not brightness-based. 13 Tauri is fainter than 5 Tauri. Always check magnitude.

- Confusing with Bayer letters-Bayer uses Greek letters (α, β, γ) and usually assigns them by brightness. So α Ursae Majoris is Dubhe, while 1 Ursae Majoris is a completely different, dimmer star.

- Missing missing numbers-Flamsteed skipped some numbers. For example, there’s no 20 Persei because Flamsteed miscounted. Always double-check star charts for gaps.

- Using outdated charts-Some old charts list Flamsteed numbers for stars that were later found to be double or variable. Modern catalogs correct this.

When in doubt, use a digital tool. Apps like SkySafari or Stellarium show both Flamsteed and HD labels side by side. You can also cross-reference with the Bright Star Catalogue, which lists Flamsteed, Bayer, HD, and HIP numbers for the 9,110 brightest stars.

Practical Tips for Star-Hopping

Here’s how to use Flamsteed numbers in real observing:

- Start with bright stars you know-like Vega or Arcturus-then move to nearby Flamsteed-labeled stars. For example, from β Bootis (Arcturus), hop to 16 Bootis, then 17 Bootis.

- Use binoculars to scan along the numbered sequence. Flamsteed stars often form loose chains across constellations.

- Keep a small notebook with your favorite Flamsteed targets and their HD/HIP equivalents. You’ll build a personal reference over time.

- When observing deep-sky objects near a Flamsteed star (like a galaxy or nebula), note the star’s number. It’s a great landmark.

For example, the famous Pinwheel Galaxy (M101) sits just 1.5 degrees from 10 Ursa Majoris. Knowing that connection makes finding it far easier than relying on coordinates alone.

What’s Next? Beyond Flamsteed

As you get more comfortable with Flamsteed numbers, start learning how to read modern catalogs. The Gaia catalog isn’t just a list-it’s a 3D map of our neighborhood in space. You can see how fast stars are moving, how far away they are, and even how old they are.

But don’t abandon Flamsteed. It’s the bridge between the old art of star-hopping and the new science of astrometry. The next time you’re out under the stars, look for 44 Leonis or 33 Cancri. You’re not just finding a star-you’re connecting with centuries of skywatchers who did the same thing, with nothing but a chart, a telescope, and patience.

Are Flamsteed numbers still used by professional astronomers?

Yes, but rarely as the primary identifier. Flamsteed numbers appear in historical references, in papers about variable stars, and in educational materials. Most professional work uses HD, HIP, or Gaia IDs for precision. But because many well-known stars (like 61 Cygni or 51 Pegasi) are still commonly referred to by their Flamsteed labels, they remain in use for clarity and tradition.

Why do some stars have both Flamsteed and Bayer designations?

Bayer used Greek letters based on brightness within a constellation, while Flamsteed used numbers based on position. For bright stars, both systems were applied. For example, α Canis Majoris is Sirius, and it’s also 1 Canis Majoris. But for fainter stars, only one system may apply. Some stars have only a Flamsteed number because they’re too dim to get a Bayer letter.

Can I find Flamsteed numbers in smartphone astronomy apps?

Most apps do, but you might need to enable them. In Stellarium, go to Settings > Sky & Viewing Options > Star Labels and check "Flamsteed". In SkySafari, tap the menu, go to Star Labels, and turn on "Flamsteed". If you’re using a chart-based app, these labels are often default.

What’s the difference between Flamsteed and the Hipparcos catalog?

Flamsteed is a positional numbering system from the 1700s, based on visual observations. Hipparcos is a satellite-based catalog from the 1990s that measured star positions with milliarcsecond accuracy. Hipparcos gives you precise distance, motion, and brightness data. Flamsteed tells you where to look. Hipparcos tells you exactly what you’re looking at.

Are there Flamsteed numbers for southern hemisphere constellations?

Flamsteed’s original catalog only covered stars visible from England, so he didn’t include many southern constellations. Later astronomers like Nicolas Louis de Lacaille extended the system to the southern sky, but their numbering isn’t as widely used. So while you’ll find Flamsteed numbers for Ursa Major or Orion, you won’t find them for Crux or Centaurus in most standard charts.