28 Dec 2025

- 0 Comments

The Moon is not just a glowing orb in the night sky. Up close, it’s a landscape of wild, ancient terrain shaped by billions of years of impacts, volcanic activity, and cooling crust. You don’t need a telescope to see some of these features-binoculars or even your naked eye can reveal the dark patches and bright spots. But if you want to know what you’re really looking at, here’s how to read the Moon’s surface: craters, maria, mountains, and rilles.

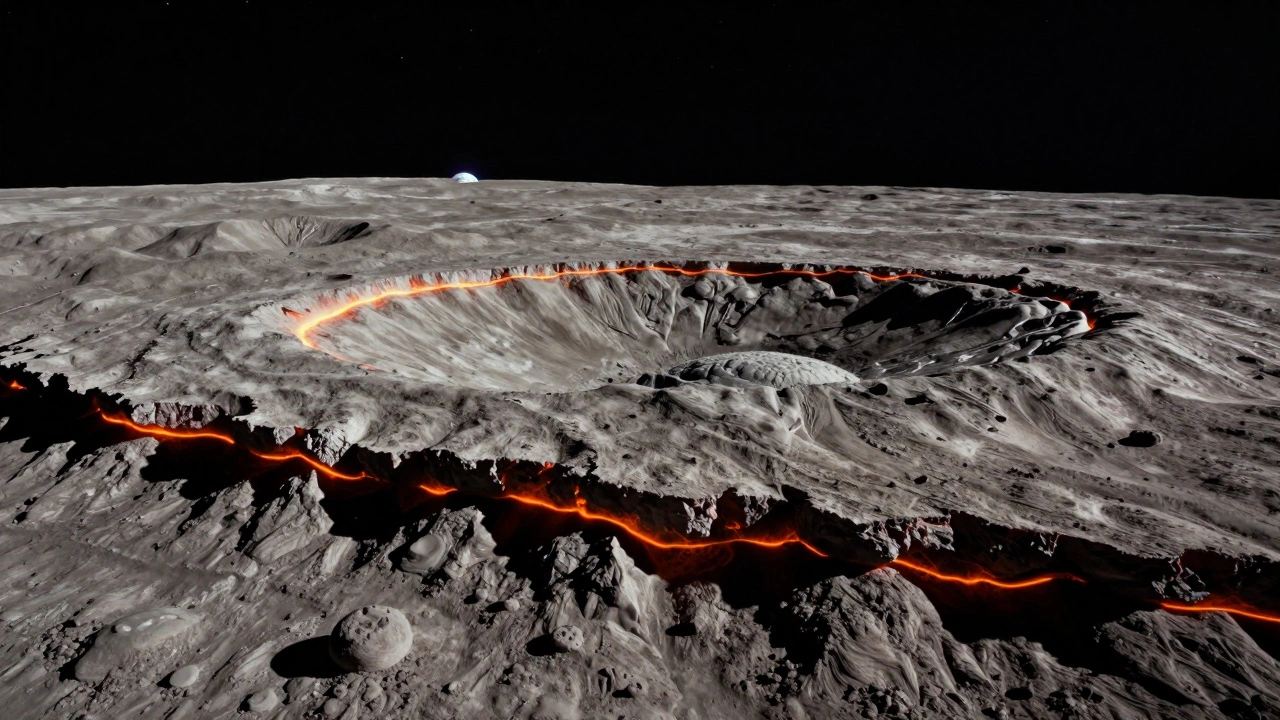

Craters: The Moon’s Scarred Skin

Craters are everywhere on the Moon. They’re the most obvious feature, and they tell a story of violent collisions. Unlike Earth, the Moon has no weather, no erosion, and no tectonic plates to erase them. That means craters from 4 billion years ago are still there, sharp and clear.

A typical lunar crater has a raised rim, a central peak, and sometimes terraced walls. The largest, like Tycho a prominent lunar crater located in the southern highlands, formed about 108 million years ago, can stretch over 80 kilometers wide. Tycho’s bright rays-long streaks of ejected material-can be seen even from Earth during a full moon. These rays are made of fresh, unweathered rock that reflects sunlight better than the older surface around it.

Not all craters are the same. Smaller ones are simple bowls. Bigger ones, like Clavius one of the largest visible craters on the Moon, located near the southern limb, have complex structures with multiple peaks and terraces. These form when the impact is so powerful that the surface rebounds after the initial collision.

Maria: The Dark Seas of the Moon

Those dark, smooth areas you see on the Moon? Those are the maria (singular: mare). The name means "seas"-early astronomers thought they were oceans. We now know they’re vast, flat plains of solidified lava.

Maria formed between 3 and 4 billion years ago, when huge asteroid impacts cracked the Moon’s crust. Molten rock from deep inside oozed out and flooded the lowlands. It cooled slowly, forming dark basalt, the same kind of rock that makes up parts of Earth’s ocean floor.

The biggest mare is Oceanus Procellarum the largest lunar mare, stretching over 2,500 kilometers across the western edge of the near side. It’s so large it looks like a single dark patch. Others, like Mare Imbrium a large circular mare formed by a massive impact, visible as a prominent dark area on the Moon’s upper left, are more defined. You can often see where the lava stopped-sharp edges where it met the higher, lighter highlands.

Maria are mostly on the near side of the Moon-the side we always see from Earth. Why? Scientists think the crust on the far side was thicker, making it harder for lava to break through. The near side was thinner, so lava flowed out more easily.

Moon Mountains: Ancient Peaks and Ranges

The Moon has mountains, but they’re not like Earth’s. No tectonic plates pushed them up. Instead, most lunar mountains were formed by impacts.

The Apennine Mountains a major lunar mountain range forming the eastern edge of Mare Imbrium, with peaks over 4,000 meters high are one of the most impressive. They ring the edge of Mare Imbrium, the giant lava plain. These aren’t volcanoes. They’re the leftover rim of a colossal impact that created the mare. When the asteroid hit, the crust buckled and pushed upward, forming peaks taller than Mount Everest.

Other mountains are volcanic. Mons Piton a solitary lunar mountain near the Mare Imbrium, known for its steep, conical shape stands alone near the edge of Mare Imbrium. It’s a remnant of an ancient volcano, not an impact rim. You can spot it with binoculars as a sharp, isolated peak.

Unlike Earth, where mountains keep growing, lunar mountains don’t change. No wind, no rain, no glaciers. They’ve stayed exactly as they were when they formed, over 3 billion years ago.

Rilles: The Moon’s Hidden Riverbeds

If you’ve ever looked closely at the Moon through a telescope, you might have noticed thin, winding lines across the maria. These are rilles-long, narrow depressions that look like dried-up river channels.

There are three kinds. The first, called sinuous rilles, twist and turn like rivers. These were likely carved by flowing lava, not water. When lava flowed across the surface, it sometimes formed channels. Later, the surface cooled and hardened, while the lava underneath drained away, leaving a hollow groove.

The Hadley Rille a sinuous rille near the Apollo 15 landing site, stretching over 100 kilometers long and up to 1 kilometer wide is one of the best-known. Apollo 15 astronauts landed right beside it in 1971 and walked along its edge. They confirmed it was formed by lava, not water.

The second type, linear rilles, are straight and long. These form along cracks in the crust, often where tectonic stress pulled the surface apart. The third type, arcuate rilles, curve gently around the edges of maria. These are thought to be the collapsed tops of lava tubes-underground tunnels that once carried lava.

These features are hard to see without a telescope. But if you have one, tracking rilles over several nights as the sunlight angle changes is one of the most rewarding lunar observations.

Putting It All Together: How to Read the Moon

Next time you look at the Moon, try this:

- Find the bright, cratered highlands-they’re the oldest parts.

- Look for the dark, smooth maria-they’re the ancient lava flows.

- Spot the bright rays around Tycho-they’re the youngest impact debris.

- Notice the sharp mountain ranges along the edges of maria-they’re impact rims.

- With a telescope, trace the winding rilles across the maria-they’re ancient lava channels.

The Moon’s surface is a history book. Craters record the bombardment of the early solar system. Maria show where the Moon was once geologically active. Mountains tell of colossal collisions. Rilles reveal how lava flowed like rivers across a world without water.

You don’t need fancy gear to start. Just a clear night, a pair of binoculars, and a little patience. Watch how the shadows change as the Moon moves through its phases. The low-angle light near the terminator-the line between day and night-makes every feature pop. That’s when craters cast long shadows, rilles turn into dark trenches, and mountains rise like cliffs.

The Moon isn’t just a rock. It’s a record of our solar system’s violent past. And you can see it all with your own eyes.

Can you see lunar features with binoculars?

Yes, binoculars are great for seeing the Moon’s major features. You can easily spot the maria (dark flat areas), large craters like Tycho and Copernicus, and mountain ranges like the Apennines. The best time is during the first or last quarter phases, when shadows make the terrain stand out. Full Moon is too bright and flat-avoid it for detailed viewing.

Why are there no craters on the maria?

There are craters on the maria, but they’re fewer and harder to see. The lava flows that created the maria covered older craters. Newer impacts still happen, but they’re smaller and get buried over time by dust. The smooth surface of the maria makes them look crater-free, but high-resolution images show they’re dotted with smaller craters.

Are lunar mountains similar to Earth’s mountains?

No. Earth’s mountains form from tectonic plate collisions, like the Himalayas. Lunar mountains mostly come from asteroid impacts-the force of the impact pushed the crust upward. Some are volcanic, but even those are shaped by low gravity and no erosion. They’re steeper, sharper, and older than Earth’s mountains.

Why do rilles look like rivers if there’s no water on the Moon?

They’re not rivers. They’re lava channels. Early scientists thought they were water-carved because they look like riverbeds. But lunar samples and rover data proved they formed when molten rock flowed across the surface. The lava carved a path, then drained away, leaving a hollow groove. No water was involved.

What’s the best time to observe lunar features?

The best time is during the first quarter or last quarter phases. That’s when the Sun is low on the lunar horizon, casting long shadows that highlight craters, mountains, and rilles. The terminator-the line dividing day and night-is where all the detail is. Full Moon washes out shadows, and new Moon is invisible. Plan your viewing around the quarter phases.