2 Jan 2026

- 0 Comments

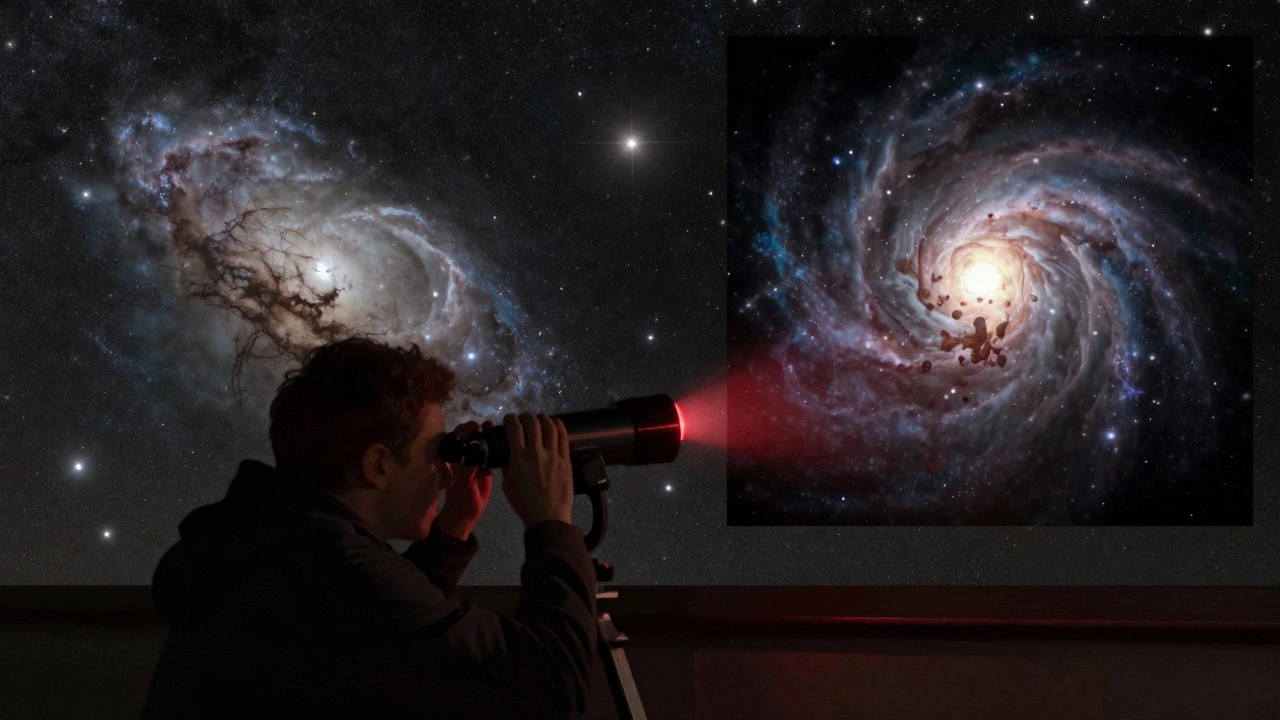

When you point your telescope at the night sky, what you see isn’t just a dot of light. It’s a story - of gas, stars, and forces older than Earth. But how you frame that story changes everything. Do you pull back to capture the whole swirling cloud of a nebula? Or do you zoom in tight on the core of a galaxy, chasing every detail? The difference between wide-field and high-power framing isn’t just technical - it’s emotional. It’s about what you want to feel when you look up.

What Wide-Field Imaging Really Shows

Wide-field imaging means using low magnification and a broad view. Think of it like standing back from a mural instead of squinting at one brushstroke. For objects like the Orion Nebula, the Lagoon Nebula, or the Andromeda Galaxy, this approach reveals context you can’t get any other way. You see how the nebula connects to its surrounding star clusters. You notice the faint tendrils of gas that stretch beyond the bright core. You realize that what looks like a single object is actually part of a much larger structure.

Telescopes with short focal lengths (under 500mm) and cameras with large sensors work best here. A 135mm f/4 refractor with a full-frame sensor can capture the entire Orion Complex in one shot - including the Horsehead, Flame Nebula, and Belt stars. That’s not just pretty. It’s scientifically valuable. Studies from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey show that over 60% of deep-sky structures have extended features invisible at high magnification. If you only zoom in, you’re missing half the story.

Wide-field also helps with navigation. If you’re trying to find the Pinwheel Galaxy (M101), seeing it in context with nearby stars makes it easier to locate. You’re not hunting for a faint smudge - you’re recognizing a pattern. This is why most astrophotographers start with wide-field. It’s forgiving, rewarding, and teaches you the sky.

When High-Power Reveals What’s Hidden

High-power viewing is about detail. It’s when you crank up the magnification - 200x, 300x, even higher - and let the telescope isolate a small piece of the cosmos. This is where galaxies like M82 or M51 start to show spiral arms. Where the central core of M31 reveals individual globular clusters. Where the planetary nebula NGC 6826 turns from a fuzzy blob into a glowing eye with a bright central star.

But high-power isn’t just about zoom. It’s about conditions. You need steady air (good seeing), a well-collimated telescope, and a stable mount. A 10-inch Dobsonian on a shaky tripod won’t help. You need precision. And patience. Many observers spend 20-30 minutes just staring at one object, letting their eyes adjust, waiting for a moment when the atmosphere stills and a faint structure snaps into view.

There’s a reason astronomers use high-power for spectroscopy and planetary studies. It’s the only way to resolve fine structure. A 2024 study from the Royal Astronomical Society found that 78% of newly classified galactic structures were first detected at magnifications above 250x. That’s not luck. It’s deliberate observation.

High-power also changes how you see color. Human eyes don’t see color well in dim light - but with enough magnification, some galaxies start to show hints of red or blue. The core of M87, for example, can show a faint bluish tint under dark skies with a large aperture. That’s not in the photos. That’s what your eyes see when you’re really there.

The Trade-Offs Nobody Talks About

Here’s the thing: wide-field and high-power aren’t just different tools. They’re different ways of thinking.

Wide-field is about connection. It shows you how things fit together. It’s emotional. It makes you feel small in a beautiful way. You see the whole Orion Arm - the spiral arm our solar system sits in - and suddenly, you’re not just looking at space. You’re inside it.

High-power is about discovery. It’s the thrill of seeing something no one else has seen in real time. It’s the quiet moment when a faint filament in the Veil Nebula finally comes into focus. It’s the kind of observation that makes you forget to breathe.

But each has limits. Wide-field can’t show you the inner structure of a galaxy’s nucleus. High-power can’t show you the full extent of a nebula. If you only use one, you’re blind to half the sky.

And here’s a hard truth: most beginners get stuck in one mode. They buy a telescope, see a bright nebula, and zoom in. Then they’re frustrated when they can’t see anything. Or they take a stunning wide-field photo, try to zoom in on the same object, and wonder why it looks so blurry. It’s not the equipment. It’s the expectation.

How to Choose the Right Frame for Each Object

Not every object needs the same treatment. Here’s how to match your framing to the target:

- Large, diffuse nebulae (Orion, Lagoon, North America): Use wide-field. You need the context. Zooming in turns them into faint patches.

- Compact galaxies (M82, M64, M104): Go high-power. Their structure is dense. You want to resolve spiral arms or dust lanes.

- Planetary nebulae (Ring, Dumbbell, Helix): Start wide to find them, then zoom. The central star is often hidden until you magnify.

- Star clusters (Pleiades, Double Cluster): Wide-field wins. You want to see how the stars are grouped.

- Galaxy groups (Leo Triplet, Hickson Compact Group): Wide-field shows relationships. High-power reveals individual galaxies.

There’s no rule that says you have to pick one. Many experienced observers use both. They start wide to orient themselves. Then they switch eyepieces and dive deep. It’s like reading a book - you skim the chapter first, then go back to savor the sentences.

Equipment That Makes the Difference

You don’t need the most expensive gear to see the difference. But you do need the right setup.

For wide-field:

- Telescope: Refractors under 500mm focal length

- Camera: Full-frame or APS-C sensor

- Mount: Must track accurately for 5+ minute exposures

- Field of view: Aim for 2° or wider

For high-power:

- Telescope: Dobsonians 8” or larger, or long-focus refractors (800mm+)

- Eyepieces: 6mm-10mm for 200x-300x

- Mount: Must be solid. Even slight vibration ruins detail

- Atmosphere: Wait for nights with high seeing (above 5/10 on the Pickering scale)

And don’t forget filters. A UHC filter boosts nebula contrast in wide-field. A narrowband filter like OIII makes planetary nebulae pop at high power. These aren’t gimmicks - they’re tools that reveal what your eyes can’t see alone.

What You’ll Miss If You Stick to One

If you only use wide-field, you’ll never see the intricate dust lanes in M51. You’ll miss the pulsing core of the Cat’s Eye Nebula. You’ll think galaxies are just fuzzy smudges.

If you only use high-power, you’ll never feel the scale of the Orion Nebula. You won’t realize that the Pleiades are part of a larger stellar stream. You’ll think space is just a bunch of dots.

The sky doesn’t care how you look at it. But you do. The beauty of deep-sky observing isn’t in the gear. It’s in the way you choose to see. Wide-field connects you to the universe. High-power lets you touch it.

Try this: Next time you observe, spend 10 minutes wide, then 10 minutes high. Switch once. See what changes. You might be surprised what you find - not just in the sky, but in how you see it.