8 Feb 2026

- 0 Comments

Ever heard someone say you need to collimate your telescope every single night? Or that a laser collimator is the only way to get it right? Maybe you’ve been told that if your stars look slightly off, your whole setup is ruined? These aren’t just tips-they’re myths. And they’re spreading faster than dust on a mirror.

Collimation isn’t magic. It’s physics. And like any physics, it gets twisted when people repeat what they heard without testing it. I’ve spent years adjusting reflector telescopes in the Pacific Northwest, under skies that range from crystal clear to thick with marine layer fog. I’ve seen good collimation save a night of imaging. I’ve also seen people waste hours chasing perfect alignment when their optics were already fine.

Myth #1: You Must Collimate Before Every Use

This is the most common lie told to new telescope owners. The truth? Most modern Newtonians and Dobsonians hold collimation for weeks, even months, if handled with basic care. I’ve used my 12.5-inch Dobson for over 30 nights in a row without touching the collimation screws. The mirror cell is stable. The truss tubes don’t shift. The primary mirror doesn’t move.

What causes misalignment? Rough transport. Dropping the scope. Extreme temperature swings. A loose secondary holder. Not normal use. If you carry your scope gently, store it upright, and avoid slamming it into a car trunk, you don’t need to collimate every time. Test it: look at a bright star at high power. If the diffraction rings are concentric, you’re good. No need to touch a thing.

Myth #2: Laser Collimators Are Always Accurate

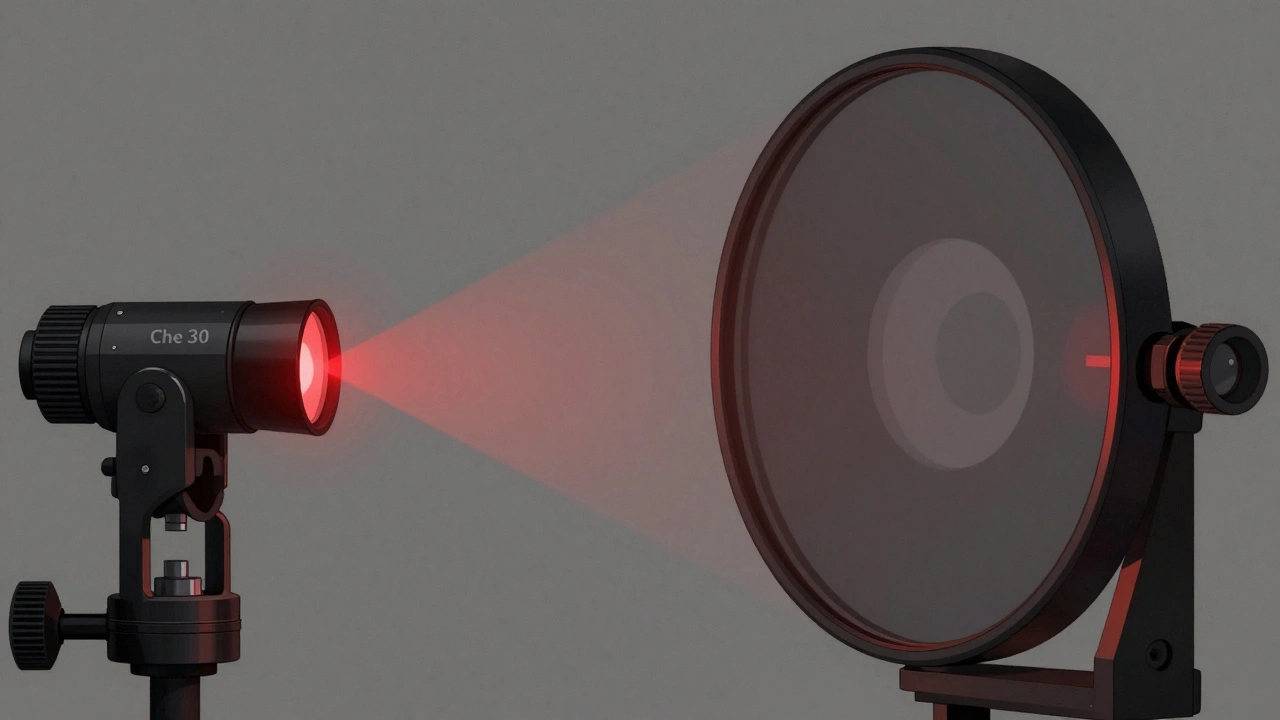

Laser collimators sound like the future. They’re easy. Plug it in, twist, done. But here’s the catch: most $30 laser collimators are cheaply made. The laser diode isn’t aligned to the barrel. The barrel isn’t centered in the focuser. You’re not aligning your optics-you’re aligning a flawed tool to another flawed tool.

I tested five popular laser collimators side by side. One was off by over 1.5 mm at the primary mirror. That’s enough to throw off star images. A Cheshire eyepiece or a sight tube? Those are mechanical. No batteries. No electronics. Just light, reflection, and your eyes. They don’t lie. If you’re serious about collimation, skip the laser unless you’ve calibrated it against a known good reference-and most hobbyists never do.

Myth #3: Perfect Collimation Means Perfect Stars

Here’s a hard truth: even perfectly collimated scopes can show distorted stars. Why? Atmospheric turbulence. Thermal currents in the tube. A mirror that hasn’t cooled down. Poor seeing. You can have your optics dialed in to within 0.1 mm, and if the air is boiling, your stars will still look like smudges.

And let’s not forget: diffraction patterns are symmetrical, but human eyes are bad at judging them. Many people think a slightly elongated star means bad collimation. It doesn’t. It might mean you’re looking at a star too low on the horizon, or your scope hasn’t acclimated to the night air. Give it 30 minutes. Let the mirror breathe. Then check again.

Myth #4: You Need a Collimation Cap or Cheshire for a Newtonian

Some guides say you can’t collimate a Newtonian without one. That’s not true. You can do it with just the eyepiece and a bright star. Here’s how: Point at Polaris or Vega. Insert a high-power eyepiece. Defocus the star until you see a disk with concentric rings. Look at the shadow of the secondary mirror. Is it centered? Now nudge the collimation screws one at a time. Watch how the shadow moves. Adjust until the shadow is dead center. Then tighten the screws. Done.

This method works because you’re not relying on tools-you’re relying on the actual light path. It’s slower. But it’s more reliable. And it teaches you how your scope actually works. You’ll understand why the secondary is tilted, why the primary needs to be angled, and how the focuser plays into the whole system.

Myth #5: Collimation Is Only for Reflectors

Reflector owners obsess over collimation. Refractors? They think they’re immune. Wrong. Even refractors need alignment. Not because the lenses move-usually they don’t-but because the focuser, diagonal, and eyepiece can shift. A misaligned diagonal can make the image appear tilted, even if the lenses are perfect.

Test it: Point your refractor at a bright star. Swap eyepieces. If the star’s position shifts dramatically in the field of view, your diagonal isn’t centered. You can fix this by adjusting the diagonal’s set screws or replacing it with a better one. You don’t need to collimate the lenses. But you do need to make sure the light path is straight.

What Actually Matters

Real collimation isn’t about perfection. It’s about consistency. You want the optical axis of the primary mirror, the secondary mirror, and the focuser to line up. Not perfectly. Just well enough that light reaches your eye without being bent sideways.

Here’s a simple rule: If your star images are round and symmetrical at high magnification, your collimation is fine. You don’t need to measure microns. You don’t need to use a laser. You don’t need to do it every night. You just need to know what to look for.

And here’s a pro tip: Take notes. Write down the date, the weather, the scope, and whether the collimation felt off. After a few months, you’ll see patterns. Maybe your scope drifts after a trip. Maybe it’s fine until winter. You’ll learn your instrument. That’s better than any YouTube tutorial.

Tools That Actually Help

Not all tools are lies. Here’s what works:

- A Cheshire eyepiece - Simple, reliable, no batteries. Shows you the center of the primary mirror and the shadow of the secondary.

- A sight tube - Lets you see the edges of the secondary and how centered it is. Great for fine-tuning.

- A bright star - The ultimate test. Nothing beats real-world performance.

- A notebook - Track your adjustments. You’ll thank yourself later.

What doesn’t work? Laser collimators under $75. Collimation apps that claim to analyze star shapes. Over-tightening screws because you’re scared of movement. Replacing parts you don’t need to replace.

Final Reality Check

Collimation is a skill, not a ritual. It’s not about getting it right once. It’s about learning how to check it, understand it, and trust it. The internet is full of people who’ve never actually looked through a scope. They’ve watched videos. They’ve read forums. They’ve repeated what they heard.

Go outside. Point your scope at a star. Look. Adjust. Observe. You don’t need perfection. You just need to know when it’s good enough. And that’s something no YouTube video can teach you.

Do I need to collimate my telescope every time I use it?

No. Most telescopes hold collimation for weeks or even months if handled carefully. Only collimate if you notice star images are distorted or if you’ve moved or dropped the scope. A quick check on a bright star is all you need.

Are laser collimators reliable for Newtonian telescopes?

Most budget laser collimators (under $75) are inaccurate. The laser isn’t aligned with the barrel, and the barrel isn’t centered in the focuser. This leads to false alignment. A Cheshire eyepiece or sight tube is more reliable and doesn’t depend on electronics.

Can a refractor telescope be out of collimation?

Yes. While the lenses themselves rarely move, the diagonal or focuser can shift. If star images appear tilted or off-center when switching eyepieces, the diagonal might be misaligned. Adjust the diagonal’s set screws or replace it with a higher-quality one.

What’s the best way to test if my telescope is properly collimated?

Point at a bright star like Vega or Polaris. Use a high-power eyepiece and defocus the star until you see concentric diffraction rings. If the rings are perfectly round and centered, your collimation is good. If they’re lopsided or the shadow of the secondary is off-center, adjustment is needed.

Why do my stars look blurry even after collimating?

Poor collimation isn’t always the culprit. Atmospheric turbulence, thermal currents in the tube, or a mirror that hasn’t cooled down can all cause blurry stars. Let your scope sit outside for at least 30 minutes before observing. If stars still look bad, then check collimation again.