28 Jan 2026

- 0 Comments

Have you ever looked up at the night sky and noticed how stars seem to dance-flickering red, then blue, then bright white-while planets just sit there, steady and calm? It’s not your eyes playing tricks. It’s physics. And it’s happening right above your head, every single night.

What causes stars to twinkle?

The technical term for twinkling is scintillation the rapid change in brightness and color of a distant light source caused by atmospheric turbulence. It’s not the star itself changing. Stars are huge, stable nuclear reactors billions of miles away. Their light is constant. What changes is the air between you and the star.

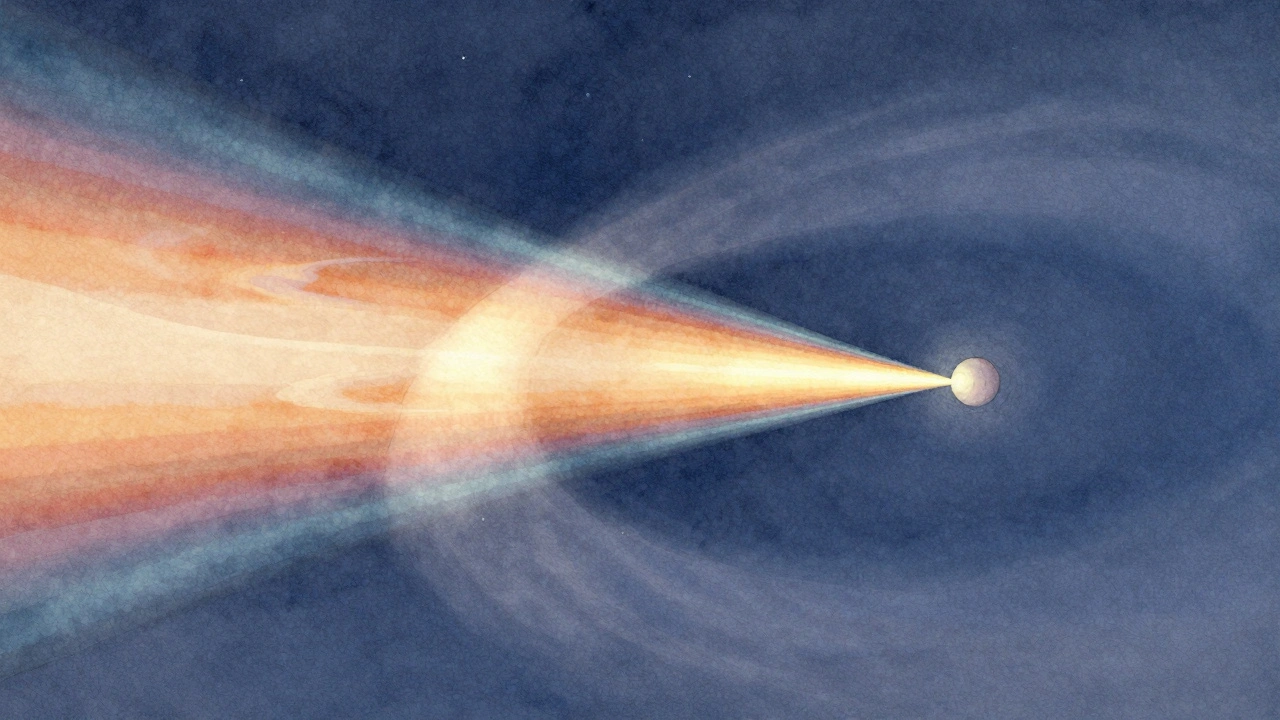

Earth’s atmosphere isn’t smooth. It’s a chaotic mix of air pockets with different temperatures and densities. When starlight passes through these pockets, it bends-slightly, rapidly, randomly. This bending is called refraction. One moment, the light focuses directly into your eye. The next, it gets scattered away. That’s why you see flashes: brighter, dimmer, colored. Blue light bends more than red, so you sometimes catch a quick flash of blue before the star dims again.

This effect is strongest when a star is low on the horizon. Why? Because the light has to pass through more air. Think of it like looking through a thick glass window at an angle-the distortion gets worse. When a star is overhead, the path through the atmosphere is shortest. That’s why stars near the zenith barely twinkle at all.

Why don’t planets twinkle like stars?

Planets don’t twinkle because they’re not point sources. That’s the key difference.

Stars are so far away that even through a telescope, they appear as single, infinitely small dots of light. Planets, on the other hand, are close enough to show a tiny disk. Venus, Jupiter, Mars-they all have measurable angular sizes. Even if they look like dots to your naked eye, they’re actually tiny disks, maybe 1 to 2 arcminutes across.

Here’s why that matters: when atmospheric turbulence bends light from a point source like a star, the whole thing flickers. But when the light comes from a small disk, different parts of that disk are bent in different directions. One edge might dim while another brightens. These changes cancel each other out. The average brightness stays steady. It’s like trying to shake a flashlight-your hand wobbles, but the beam stays mostly stable. A star is like a single LED. A planet is like a cluster of LEDs glowing together.

Try this: on a clear night, compare a bright star like Sirius to Jupiter. Sirius will jump around, changing color. Jupiter will glow with a steady, golden light. That’s not luck. That’s geometry.

How does this affect stargazing?

Scintillation isn’t just a pretty effect-it’s a real obstacle for serious observers. If you’re trying to see fine details on Mars, or split a tight double star, atmospheric turbulence is your enemy. Astronomers call this seeing. Good seeing means steady, sharp views. Bad seeing means everything wobbles.

That’s why professional observatories are built on mountaintops: above much of the atmosphere. Places like Mauna Kea in Hawaii or the Atacama Desert in Chile have stable air layers and minimal turbulence. Even amateur astronomers learn to wait for moments of calm. You’ll notice the stars suddenly stop twinkling for 10 or 20 seconds. That’s a pocket of smooth air passing overhead. That’s your chance to catch a glimpse of a faint nebula or a moon’s crater edge.

Telescopes can’t fix bad seeing. A bigger lens won’t help. A better eyepiece won’t help. Only time and patience will. Some nights, the air is still. Others, it’s like looking through a heat shimmer on a highway. You can’t control it. But you can learn to read it.

Why some stars twinkle more than others

Not all stars twinkle the same. Brighter ones seem to twinkle more, but that’s partly because you notice them. The real difference comes from color and position.

Blue stars-like Rigel in Orion-twinkle with more vivid color shifts because their shorter wavelengths bend more easily. Red stars-like Betelgeuse-change less in hue, but their brightness still pulses. Stars near the horizon, like Arcturus when it rises in the east, can appear to flash like a traffic light. That’s because their light travels through more of the lower, turbulent atmosphere.

And then there’s the Moon. You might think it twinkles. It doesn’t. Not really. The Moon is bright, large, and close. Its light is too strong and too spread out to be affected by scintillation. What you might see is a shimmer around the edges during high winds-that’s not twinkling. That’s air moving across your line of sight.

What about planets near the horizon?

Even planets can seem to flicker if they’re low in the sky. Venus, when it’s just above the horizon at dawn, can appear to pulse. Jupiter, when it’s rising, might look a little wobbly. But it’s not true scintillation. It’s a mix of atmospheric distortion and the planet’s brightness overwhelming your eye’s ability to process steady light. The disk is still there. The cancellation effect is still working. It’s just being tested.

If you watch carefully, you’ll see the planet’s light doesn’t change color like a star. It just gets slightly blurry or hazy. That’s the difference. Stars change color. Planets blur. One is physics. The other is optical noise.

How to use this knowledge

Next time you’re outside, don’t just look up-observe. Pick out a bright star and a bright planet. Watch them side by side. Notice how one dances and the other holds still. That’s your first lesson in atmospheric science.

If you’re into astrophotography, you’ll know this well. Long-exposure shots of stars show trails of color and motion. Planets? Sharp, stable disks. That’s why planetary imaging doesn’t need fancy adaptive optics-it just needs time. Stack hundreds of frames, and the turbulence averages out. The disk stays.

And if you’re trying to find your way around the night sky, use twinkling as a clue. If a bright point of light is dancing, it’s probably a star. If it’s steady, it’s likely a planet. Ancient astronomers didn’t know about refraction, but they knew: steady lights were different. They called them “wanderers.” We call them planets. They were right.

Final thought: The sky is alive

Twinkling isn’t magic. It’s air moving. It’s temperature shifts. It’s wind at 10,000 feet, unseen, but felt in the light. The same air that makes your breath visible on a cold morning is bending starlight above you.

Stars twinkle because they’re far away and small. Planets don’t because they’re close and wide. That’s it. No complex math. No hidden forces. Just physics, happening right now, as you read this.

Go outside tonight. Find a quiet spot. Let your eyes adjust. Watch the sky. The stars are dancing. The planets are waiting. And you’re seeing the atmosphere itself, in real time.

Why do stars twinkle but planets don’t?

Stars twinkle because they’re so far away they appear as single points of light. Earth’s atmosphere bends their light randomly as it passes through pockets of hot and cold air. Planets are much closer and appear as tiny disks, not points. Light from different parts of the disk gets bent in different directions, canceling out the flickering effect. So planets stay steady.

Can planets ever twinkle?

Planets rarely twinkle visibly, but when they’re very low on the horizon, atmospheric turbulence can make them appear to shimmer or blur. This isn’t true scintillation-it’s the planet’s light being distorted by thick air near the ground. Even then, the color doesn’t shift like a star’s. You’ll see haziness, not flashing colors.

Does the Moon twinkle?

No, the Moon doesn’t twinkle. It’s too close and too large in the sky. Its light comes from a broad surface, not a point, so atmospheric distortion averages out. You might see a slight shimmer around the edges on windy nights, but that’s air moving across your view-not the Moon changing.

Why do stars change color when they twinkle?

Different colors of light bend at different angles when passing through air of varying density. Blue light bends more than red. When turbulence shifts the path of a star’s light, sometimes more blue reaches your eye, sometimes more red. This creates quick flashes of color-blue, then white, then orange. It’s like a prism made of wind.

Is scintillation worse in some places than others?

Yes. Scintillation is strongest near the horizon and in areas with high ground-level turbulence-like cities, valleys, or coastal zones. In Portland, for example, cold air sinking from the hills on clear nights can create strong layers of air that make stars near the horizon flicker badly. At high elevations, like mountain tops, the air is calmer, and twinkling is much less noticeable.